Spring 2017, Vol. 49, No. 1

President Wilson addresses Congress on April 2, 1917, to call for a declaration of war against Germany. (165-WW-47A-4)

On April 2, 1917, Washington buzzed with excitement.

While “a soft fragrant rain of early spring” poured over the city, thousands of people clogged the streets and hotels; others stood near the White House waving small American flags. President Woodrow Wilson would address a special session of Congress that evening about “grave matters” and was expected to ask for a declaration of war against Germany.

The larger-than-usual crowds were in the nation’s capital to witness this historic occasion. Exactly when Wilson would speak was unknown. The 65th Congress was set to meet at noon, and with a long list of organizational matters to deal with, they would be busy most of the day.

Wilson spent the morning playing golf with his wife, Edith. Right after having lunch with two cousins, the President was notified by the House that its business would conclude by five o’clock. Wilson replied that he would arrive at 8:30 in the evening. In the afternoon he briefed Secretary of State Robert Lansing and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels in the State, War, and Navy Building across from the White House. He learned that a German U-boat had sunk the armed merchant ship Aztec, killing 12 of the crew. To Wilson the tragedy added fuel to his upcoming request for a declaration of war. At 6:30 p.m. Wilson sat down for dinner with family members and his adviser, Col. Edward M. House. During the meal, “we talked,” House recalled, “of everything excepting the matter at hand.”

House should not have been surprised. As the most trusted member of Wilson’s staff with limitless access to the President, he saw firsthand how much strain writing the speech had caused his boss. More than ever, he needed to relax. Composing the speech took three days, mostly because Wilson could not concentrate. Instead of putting pen to paper, he found excuses to talk privately with Edith, meet with staff members, play pool, or read for pleasure.

When Wilson forced himself to work on the speech, he sat alone in his office reviewing press reports and editorials in the New York Times. He hoped to get a pulse on what course of action his countrymen wanted him to take. First he drafted an outline, then composed his thoughts in shorthand before a corrected version was transferred into longhand. After attending church on April 1, Wilson completed the speech on a Hammond typewriter, sealed it in an envelope, and handed it off to the Public Printer, where copies were made and distributed to the press.

Wilson Now Favors a U.S. Role in Europe

President Woodrow Wilson. (111-SC-11761)

In his speech before Congress, Wilson laid out evidence of why the United States should now join its allies, Great Britain and France, in the European war that had been raging since August 1914—at the cost of enormous bloodshed and destruction that showed no end in sight. Having just won reelection on a platform of keeping America out of the war, Wilson was now ready to change his approach and ultimately concede that the United States should no longer remain on the sidelines.

At any time over the past two years, the rapidly deteriorating relations between his administration and the German government could have led Wilson to the same conclusion

On May 7, 1915, a German U-boat sank the British passenger ship RMS Lusitania off the southern coast of Ireland. One hundred and twenty-eight Americans were among the 1,200 killed. Wilson responded cautiously by protesting the sinking and demanding that in the future, Germany protect American lives. Germany rightly argued that the Lusitania carried war materiel destined for Great Britain and, therefore, was a legitimate target torpedoed in a war zone.

Wilson later invoked stronger rhetoric. He warned Berlin that any future sinking of ocean liners would be considered a deliberate and unfriendly act. Despite the growing friction between the United States and Germany, Wilson still wanted no part of the war even as he was slowly preparing his country for the inevitable.

On June 3, 1916, the National Defense Act, which would incrementally increase the regular Army to 175,000 and the National Guard to 400,000, was enacted. Training camps for officers, such as the Plattsburgh camp in upstate New York, sprang up around the county. By now an untold number of Americans were already fighting in the war. They either went across the border to join the Canadian forces or sailed directly to Europe to serve with the British, French, and Italians as ambulance drivers, doctors, and pilots. U.S. Army officers in Europe, placed as observers and attachés, sent back reports on the latest Allied and German operations, tactics, and strategies. Their observations were widely distributed through the Army’s professional journals and magazines and studied at its War College.

The following year, the United States and Germany grew even further apart. On January 31, 1917, German Ambassador Count Johann Heinrich von Bernstorff and Secretary of State Lansing met privately. As instructed to do at the stroke of midnight, von Bernstorff advised Lansing that U-boat attacks in the Atlantic would resume. Wilson took the unwelcome news hard, telling his private secretary Joseph Tumulty, “this means war.” But for now, this was just Wilson speaking out loud.

Germany Seeks to Draw Mexico into War with U.S.

Tension between the two countries reached a boiling point after the White House learned about the “Zimmermann telegram.” On February 24, 1917, a telegram, intercepted by Great Britain the previous month, was made known. Sent by German foreign minister Arthur Zimmermann to his ambassador in Mexico, the message explored the idea of creating an alliance with the Mexican government in the event that Germany went to war with the United States.

If that event became reality, Zimmermann wanted Mexico to declare war on the United States and request that Japan cooperate as well. In return, Germany would financially aid Mexico and, once the United States was beaten, support Mexico in retaking Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas, which had been lost during the Mexican-American War in 1848. Wilson released the telegram to the press, and the American people exploded with outrage.

Unbending to the public cry for immediate war, Wilson did not want to make matters worse. Instead, he sought to punish the Germans by instructing Lansing to break diplomatic relations with Germany. A month later, Wilson asked Congress to allow the arming of U.S. flag merchant ships but was turned down. Using his executive powers, he then directed Secretary of Navy Josephus Daniels to place naval armed guards aboard American vessels. Even with guns fixed on the decks of civilian ships, they proved no match for the deadly U-boats. On March 20, Wilson called a cabinet meeting to gauge feelings about going to war. Each of his cabinet members thought war against Germany the only option.

Now on the eve of delivering the most important speech of his political career, Wilson agonized about his message and how it would lead the country to war. He sought friendly reassurance and called on Frank I. Cobb, a journalist with the New York World and an unabashed supporter of Wilson. The message from the President did not reach Cobb until late on April 1, and he did not arrive at the White House until around 1 a.m.

“The old man was waiting for me,” he wrote, “sitting in his study with the typewriter on his table.” Cobb, who at 48, was only 13 years younger than the President, recalled: “I’d never seen him so worn down. He looked as if he hadn’t slept, and he said he hadn’t.”

Men from New York are on their way to train at Camp Upton. (165-WW-476(13) )

A Restless President Talks of War with Friend

The two friends spoke for much of the morning. Wilson did most of the talking, telling Cobb that “once I lead the people into war they’ll forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance.” Wilson further opined: “To fight you must be brutal and ruthless, and the spirit of ruthless brutality will enter into the very fiber of our national life, infecting Congress, the courts, the policeman on the beat, and the man on the street.”

At 8:20 p.m. on April 2, a black Cadillac limousine carrying President and Mrs. Wilson—accompanied by Tumulty and White House physician Dr. Cary Grayson—drove through the Executive Mansion gate. A cavalry escort met the car, and together they traveled one and a half miles to the Capitol. Through the evening, a light drizzle fell on its dome, and the large American flag on top was illuminated by floodlights. At 8:30 p.m., they arrived at the Capitol, where more cavalry, sharply dressed and sabers drawn, greeted the President. Wilson was led into an anteroom to compose himself.

Unbeknownst to him, Atlantic Monthly editor Ellery Sedgwick was also in the room, but concealed from Wilson’s view. Sedgwick watched as Wilson walked to a mirror and just stared for a few moments. From the reflection Sedgwick saw the President’s “chin shaking and his face flushed.”

Wilson then left the room, walked through a corridor, pushed open the swinging doors, and entered a hallway. He was directed into the chamber of the House of Representatives, where he could see that every seat was filled, and in the galleries, people stood bunched together with barely enough room to breathe. At 8:32 p.m., Speaker of the House James Beauchamp “Champ” Clark announced, “The President of the United States.”

A Nervous President Asks to Take Nation to War

Wilson approached the rostrum and shuffled his note cards. As he prepared to speak, the Supreme Court justices, seated directly in front of him, arose and began to clap. They were joined by everyone else in the packed room. Several seconds elapsed before the thunderous applause quieted down.

As the President began to speak, the audience heard his voice quiver and saw his hands shake while a nervous expression replaced his normally confident glow.

Without deviating, Wilson described German attacks by its U-boats and spies. Hospital ships and vessels carrying relief supplies to Belgium, he said, were fair game to the enemy sea hunters. This was “warfare against mankind,” the President assured his audience, “and the United States could not choose the path of submission and suffer the most sacred rights of our nation and our people to be ignored or violated.”

Then he came to the main reason for the address: “I advise that the Congress declare the most recent course of Imperial German Government to be in fact nothing less than war against the government and people of the United States.”

From here, Wilson outlined the war aims, and stressed that the nation’s motive “will not be revenge or the victorious assertion of the physical might of the nation, but only the vindication of right, of human right, of which we are only a single champion.”

Furthermore, the President declared, “there is one choice we cannot make, we are incapable of making,” and that is “we will not choose the path of submission.”

Women say farewell to soldiers deployed for war. (165-WW-476-1)

Congress Cheers Louder as Wilson Outlines Aims

Wilson had whipped the House chamber into a frenzy, and the lawmakers cheered loudly. Chief Justice Edward Douglass White dropped a big hat he had been holding so he too could raise his hands to clap. But the cheering only grew louder when Wilson announced his hope that the war would “keep the world safe for democracy.”

As his address concluded, Wilson stressed: “But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts—democracy. . . . To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, . . . with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.”

At 9:11 p.m., 38 minutes after he started, Wilson finished speaking. As his voice trailed off, there was a moment of silence interrupted by loud applause—even louder than when he had first begun the address.

Other than shaking a few outstretched hands as he left the rostrum, including one extended by his biggest critic, Republican Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, Wilson did not linger at the Capitol. He got back into the Cadillac and quickly returned to the White House. There the President gathered in the Oval Office with his wife, daughter Margaret, and Colonel House to reflect on the speech and its ramifications.

“I could see,” House commented in his diary, “that the president was relieved that the tension was over and the die cast.” Later that evening Wilson spoke privately with Tumulty in the Cabinet Room and allegedly told him: “Think what it was they were applauding. My message today was a message of death for our young men. How strange it seems to applaud that.”

Hours later, newspaper editorials around the world commended Wilson. “No praise can be too high for the words and the purposes of the President,” wrote one editor. “How vastly more impressive and conclusive this arraignment of German aggression becomes,” wrote another, “from the fact that the President has so steadfastly held on a patient and forbearing course.”

A prominent London newspaper declared that “the cause in which America draws a sword and the grounds on which the President justifies the momentous step he has taken are auguries that the final outcome will be for the happiness and welfare of mankind.” German editors and journalists, not surprisingly, wrote negatively about Wilson and his actions.

On April 4 the Senate voted overwhelmingly to approve Wilson’s call for war, 82 to 6, and two days later, Good Friday, the House of Representatives took up the war question. At four in the morning, exhausted after debating for most of the day, 373 members responded yea, while six answered nay. Among the handful of nays was Jeannette Rankin, a Republican representative from Montana and the first woman ever elected to the House. Rankin was an ardent suffragist and pacifist, and she made it clear that “I want to stand by my country, but I cannot vote for war.”

Pershing Seeks to Lead U.S. Troops in Europe

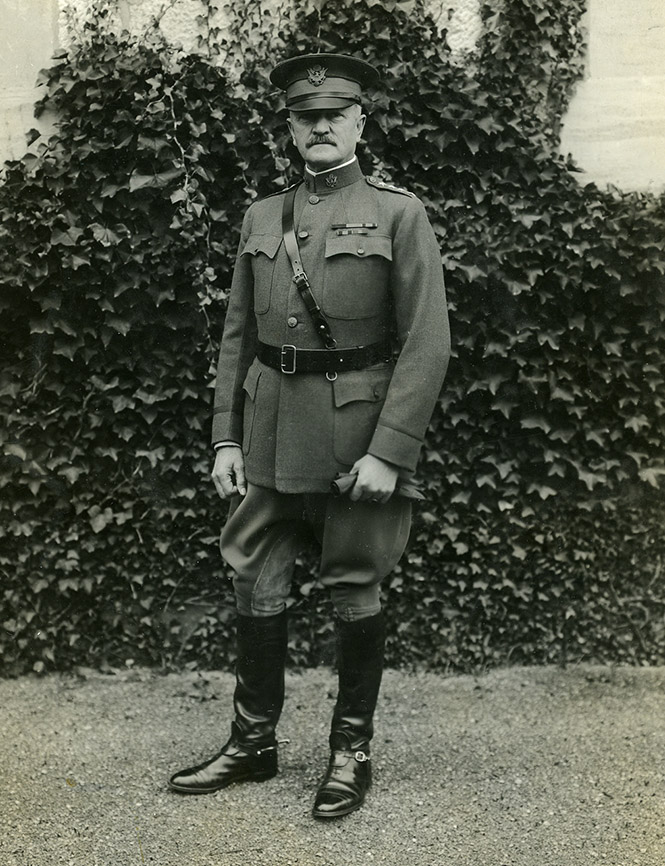

Gen. John J. Pershing commanded the American Expeditionary Forces after the United States entered the European war. (111-SC-26646)

On April 6, 1917, the war resolution arrived at the White House just as Wilson finished his lunch. Edith handed her husband a gold pen, and war was formally declared against Germany at 1:18 p.m. Rudolph Forster, the President’s executive clerk, informed the reporters waiting nearby. At the Navy Department, Secretary Daniels ordered a naval officer to step outside and signal in code to another officer that war had been declared. From there the news was flashed around the world by wireless operators.

The following day, the White House mailbox was crammed with letters supporting the President.

In the pile was a note sent by John J. Pershing. The 57-year-old major general was congratulatory, but his message had an ulterior motive. Just back from a year in Mexico chasing after Pancho Villa with his Punitive Expedition, Pershing expected that at some point the United States would join the war in Europe, and he desperately wanted to lead the American military contingent should the opportunity present itself.

In his brief letter to Wilson, Pershing tossed his hat in the ring: “As an officer of the army, may I not extend to you, as Commander-in-Chief of the armies, my sincere congratulations upon your soul-stirring patriotic address to Congress on April 2nd. Your strong stance for the right will be an inspiration to humanity everywhere, but especially to the citizens of the Republic. It arouses in the breast of every soldier feelings of the deepest admiration for their leader. I am exultant that my life has been spent as a soldier, in camp and field, that I may now the more worthily and more intelligently serve my country and you.”

Expecting that his letter might get overlooked, Pershing also wrote Secretary of War Newton D. Baker and reiterated what he had previously told the President: “In view of what this nation has undertaken to do, it is a matter of extreme satisfaction to me at this time to feel that my life has been spent as a soldier, much of it in campaign so that I am now prepared for the duties of this hour,” Pershing preached. “I wish thus formally, to pledge to you, in the personal matter, my most loyal support in whatever capacity I may be called upon to serve.”

Pershing Is Selected As Top U.S. Leader

In defense of his request, the fact remained that no officer in the U.S. Army was more qualified to lead a fighting force in Europe than Pershing. Much of his military career had been spent abroad, where he represented his country as a soldier and a politician. An 1886 West Point graduate, Pershing served with a cavalry regiment on the frontier in New Mexico, taught military science at the University of Nebraska, was cited for bravery during the Spanish-American War and the Philippine Insurrection.

Pershing’s impressive work as both a department commander and military governor helped him catapult over a long list of other junior officers for promotion to brigadier general. Pershing’s stellar military career was marked by tragedy when a fire on August 27, 1915, at the Presidio in San Francisco took the life of his wife and three of his four young children. Deeply sadden by the loss, Pershing put all of his energy into Army service.

Whether or not Secretary of War Baker read Pershing’s note, he already knew about the general’s leadership ability and, in May 1917, selected him to command what would become the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF). Baker later said there was never any indication of regret over this decision, though he did agonize over making the selection. After the war, he revealed the ideal partnership between a war secretary and his commanding general: “Select a commander in whom you have confidence; give him power and responsibility, and then . . . work your own head off to get him everything he needs and support him in every decision he makes.”

The only other serious candidate for the position was former chief of staff and recipient of the Medal of Honor, Maj. Gen. Leonard Wood. Even with his impressive credentials, the Wilson administration was wary of him. Wood had health concerns and lacked recent field experience, and the scuttlebutt around Washington was that he had presidential aspirations and might be a political threat. He also had close ties to Theodore Roosevelt, whom Wilson despised. Pershing raised none of these concerns.

Standing about six feet tall, Pershing’s trim physique was ramrod straight; a full head of sandy hair and a neatly groomed mustache accented a face mostly absent of wrinkles. He had aged somewhat from the heartbreak of tragedy, but Pershing still looked younger than his years and could have served as a model for the Army’s recruitment posters.

Countless Army Signal Corps photographs show only one side of Pershing’s demeanor: that of a stern military officer sitting at his desk, on horseback, or reviewing troops in the field. Privately, to those he let into his inner circle, Pershing was sensitive, warm, and caring. One Army officer described the World War I commander this way: “Pershing inspired confidence but not affection. He won followers, but not personal worshipers, plain in word, sane and direct in action.”

Nation Goes to War with Meager Forces

American soldiers embark for the front in France. (165-WW-289C-7)

With Pershing at the helm as AEF commander, President Wilson committed the United States to war with a skeleton fighting force. The U.S. Army comprised slightly more than 127,000 officers and men in the Regulars and about 67,000 more federalized National Guardsmen. Right after the war declaration, a large number of patriotic Americans rushed to enlist, but there still weren’t enough men to bolster the meager armed forces. Left with no other choice, Wilson ordered the War Department to organize a draft, with all males between the ages of 21 and 30 (later extended to include ages 18 to 45) required to register. Ten million men complied, and the Army eventually drafted 2.7 million.

Training camps were hastily constructed in the South and Southeast, where the new U.S. soldiers would spend six months learning the rudiments of war from officers who, in many cases, knew only slightly more than they did. Both the British and French helped out by sending officers across the Atlantic to assist with the instruction.

It was an eye-opening experience for the foreigners, some of them veterans of Verdun and the Somme. They traveled from one training camp to another, preaching trench warfare to young recruits who carried wooden guns and were without proper uniforms and equipment. It was hard to point out the benefits of grenades, flamethrowers, and artillery when many American troops would not encounter these modern weapons until they reached the western front.

It would take about nine months to train most American Army divisions (just over 27,000 officers and men) before they could be deployed overseas. Slow in organizing, but quick to learn how to fight on the Western Front battlefields, Pershing’s troops made an immediate contribution when they began to arrive and turned the tide of the war in favor of the Allies.

Doughboys, as they were nicknamed, were victorious at Cantigny, Belleau Wood, St. Mihiel, St. Quentin Canal, and the 47-day Meuse-Argonne offensive. When the Armistice took effect at 11 a.m. on November 11, 1918, more than 2 million soldiers, sailors, marines, nurses, telephone operators, and civilians were serving in Europe. Additional troops fought in faraway Siberia. Another 2 million troops were still in the United States, preparing to serve overseas, but the Armistice arrived before they could go abroad.

Americans paid a heavy toll for their Great War contribution. More than 50,000 died in combat while an almost equal number perished from accidents and disease—most as the result of the influenza epidemic.

Over the course of 18 months, the Americans rallied to the aid of its Allied partners and backed up President Wilson’s proclamation to “keep the world safe for democracy.”

Mitchell Yockelson is an investigative archivist with the National Archives Archival Recovery Program. He has also written two books on World War I, including Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing’s Warriors Came of Age to Defeat the German Army in World War I.

Note on Sources

Woodrow Wilson’s correspondence is published in Ray Stannard Baker, Woodrow Wilson Life and Letters: Facing War, 1915–1917, volume 6 (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1937) and in Arthur S. Link, editor, The Papers of Woodrow Wilson (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1966–1994).

Three useful secondary sources on the Wilson administration are A. Scott Berg, Wilson (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 2013); Arthur S. Link, Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace, 1916–1917 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965); and John Milton Cooper, Jr., Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009).

Two thorough studies of the United States in World War I are Edward M. Coffman, The War to End All Wars: The American Military Experience in World War I (New York: Oxford University Press, 1968) and Meirion and Susie Harries, The Last Days of Innocence: America at War, 1917–1918 (New York: Random House, 1997.

Other works consulted for this article are

Mark Sullivan, Our Times, The United States, 1900–1925, volume 5: Over Here: 1914–1918 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933); Lee A. Craig, Josephus Daniels: His Life and Times (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2013); Ray Stannard Baker, Woodrow Wilson Life and Letters: Facing War, 1915–1917, volume 6. (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1937); Frank E. Vandiver, Black Jack: The Life and Times of John J. Pershing (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 1977); Mitchell Yockelson, Forty-Seven Days: How Pershing’s Warriors Came of Age to Defeat the German Army in World War I (New York: NAL, 2016); and Frederick Palmer, John J. Pershing, General of the Armies: A Biography (Harrisburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1948).

Articles published in Prologue do not necessarily represent the views of NARA or of any other agency of the United States Government.

Learn more about . . .